Having done a number of blogs about completed (or nearly-completed) buildings, I thought I’d do a slightly different one about the process of design. How does it differ (in fact, does it differ) from the design process for other projects?

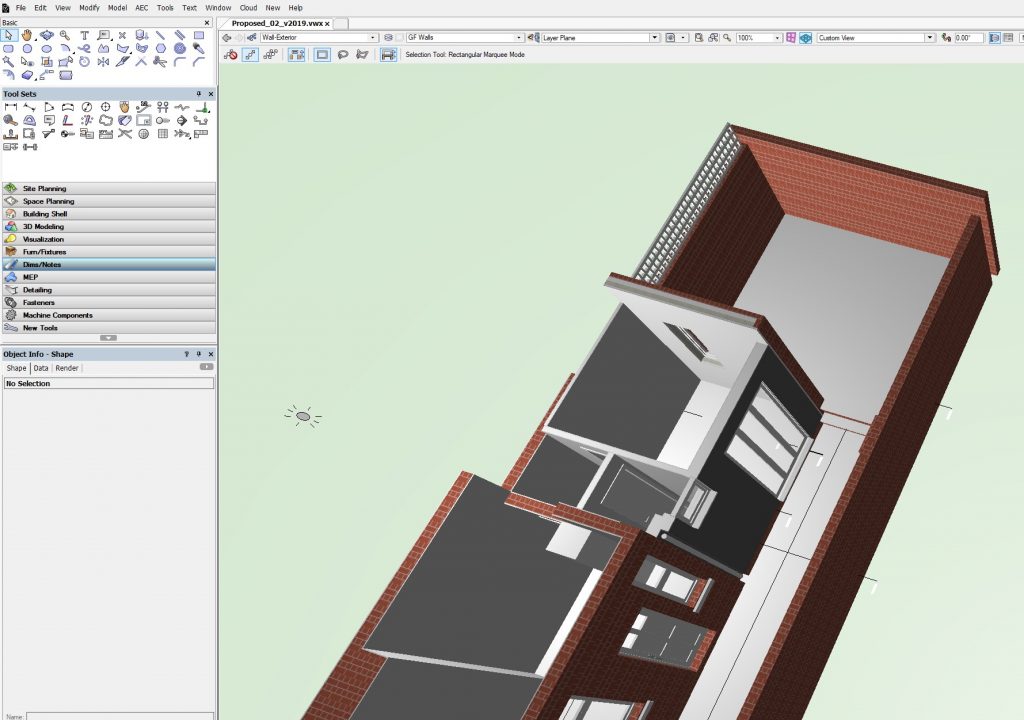

All of my design work is done on 3D CAD software – I use Vectorworks Architect, which is a building-specific application. Building up a design involves using “real” elements – walls of sophisticated multi-layer make-up, realistic windows and doors, accurate staircases, all incorporated into storeys and all viewable in many ways.

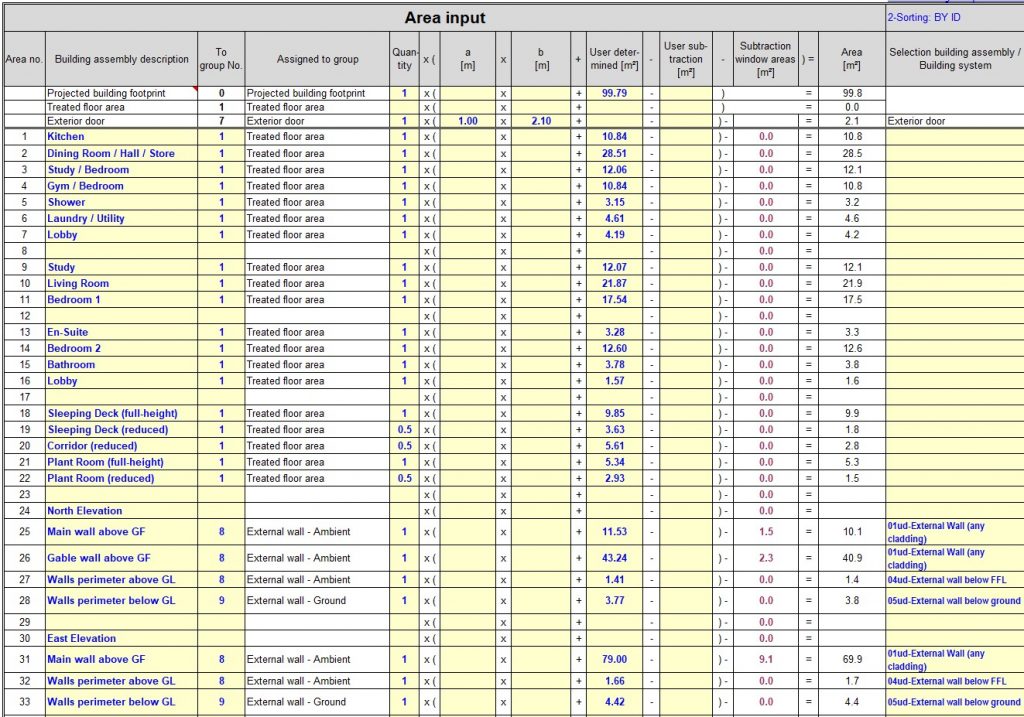

At the same time, I’ll have the Passivhaus PHPP software running on screen – this is effectively a huge, multi-tabbed Excel spreadsheet. As the design of elements becomes firmed up, geometry information is put into PHPP – areas of external walls, window sizes and types, floor areas of each space as the plan gets developed, etc.

The third of four essential applications is my visualisation software, Artlantis. By exporting the CAD model into Artlantis, I can then add photorealistic materials and finishes, orientate the building to get accurate sunlight falling onto and into it, and easily “walk” around it inside and out. I can drop furniture into it (to replicate – in size at least – any essential items the client wants to accommodate) and also export images to use in photomontages.

The modelling of sunlight is especially useful – both for exploring daylighting of internal spaces and also for getting accurate figures for the impact of external shading.

This trio of tools accompanies most of the design process; Vectorworks then produces formal plans / sections / elevations from the 3D model, and Artlantis produces powerful images which helpfully illustrate Design Statements, with Photoshop being used where photomontages are required to show a building in context. PHPP is used to build up a picture of the energy performance, a tool to explore “what ifs” and get the proposals to the point where the design should achieve Passivhaus certification, subject to quality control on site.

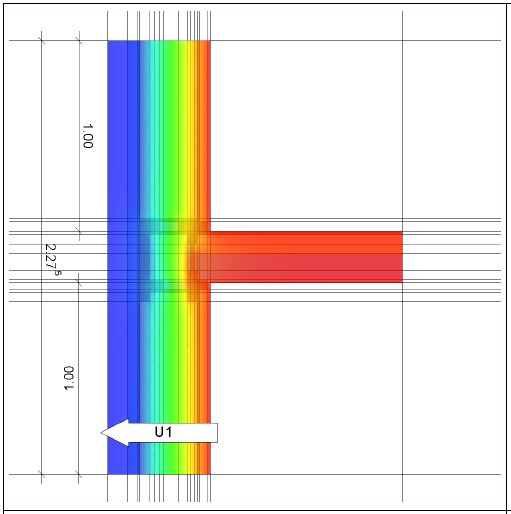

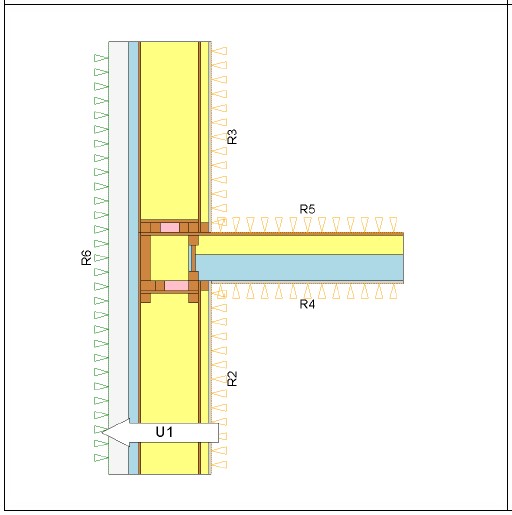

However, there’s one other very useful tool. Passivhaus works because we put in a lot of detail, and this includes looking at cold-bridging (any possible short-cuts for heat through the structure – usually at junctions such as floor or roof edges). For this I use PsiTherm, which enables accurate modelling of junctions. Again performing “what ifs” allows best solutions to be worked out, and the resulting figures used within PHPP to give accurate heat loss projections.

As a process – for an architect and Passivhaus Designer – this is really satisfying and for clients it’s very efficient and fast – I’m crunching all my own numbers and have, over the years, gained a “feel” for how design impacts on energy performance. I could farm the techie bits out to consultants but would then lose that direct connection between science and art. Plus, of course, the slightly nerdy bit of me that rather likes numbers would feel cheated, and we can’t have that. I often use PHPP on non-Passivhaus jobs just to get an accurate picture for energy performance, and enable sensible decisions about space heating technologies.

Passivhaus design isn’t utilitarian and isn’t about restricting creativity. It’s the demands of the brief that make buildings interesting. Designing places which work well – and will continue to work well in our changing climate – and which also bring joy, is about as much fun as being an architect gets. Throw in interesting clients and supporting cast – yes, maybe that’s you – and it gets better still.