I’ve been having conversations in my My Future York work about how designers can engage with the public around the process of design – not the outcomes from it, the “early sketches”. But the process which leads to these – which is where the challenges of the brief get addressed, where compromises are considered, and where looking at everything afresh can bring surprising new ideas. It’s not easy to get this message across , so I decided the best thing to do was to pick apart a project I’m working on, and blog it. Here we go.

I have a project where clients have bought a house with an attached plot, with consent for a new house on it. They don’t like the design of the proposed house (above) – and I don’t blame them. It’s been designed in a “dormer-bungalow” style, despite there being no similar buildings in the village; it’s been apologetically squished downwards to be lower than nearby buildings, resulting in mean ceiling heights to living spaces, and likelihood of frequent bedroom cursing as heads strike low sloping soffits. It’s a cold-bridging nightmare when we’re trying to get good energy performance. But – and here’s a tricky thing – the foundations and ground slab are already built (photo below). So here’s the challenge:- how to put something there which works better, and celebrates the site more, while sticking with the existing ground floor loadbearing walls?

The clients had given me a brief for what they wanted from the house; in common with all my projects I’d avoided asking what rooms they wanted and focused on asking how they wanted to live there. They described life which circled around the kitchen, with patterns of work (even pre-Covid) meaning it was good to have a central place for casual contact with the family, and where food clearly played (as it does in so many lives) a central role in bringing people together, whether living in the house or visiting. They described the issues with a current through-living space and wanted to be able to separate off TV noise.

They also wanted the inside and outside to feel connected, both visually and practically with continuous floor level between them. They noted the setting of the site and the fact there was good stuff beyond it – a long and wild garden next to it has ancient ponds. They wanted a home that felt light, that was basically spatially fairly simple but used good materials and incorporated detail in key places to give it character.

How to go about this? Well, first off, I wonder where living space should be? Connection with the pleasant garden would be good – kitchen and dining downstairs kind of makes sense in order to be able to pull a table outdoors in summer. But the living room? There are wild ponds nearby, which could be seen from first floor but not from ground level; what about stacking the living room above the kitchen and dining room? How to get it facing the right way though; the rectangular footprint sets the direction of the main roof ridge, leaving the end gables facing at right-angles to the view of the ponds. But putting a dormer gable facing the ponds would work, opening up two more possibilities – a shallow balcony with a folding glazed screen to open up that view, and pairing a second gable dormer on the other face of the main roof; open everything up to the full height inside and you have a fabulous space with an axis lining up with the ponds.

All of this gave a “living end” to the house, oriented at right angles to the longest dimension and the ridge of the roof. It allowed for a fairly concealed “open” end of this with views and physical connection with the garden and beyond, and on the other, approach side of the house a more enclosed, traditional appearance.

Next, let’s think about the heights. That roof gives some height to that living room – what about elsewhere? At ground floor level raising the ceiling to 2.7m gives a much airier feel than the “standard” 2.4m, with only 0.3m extra height. Upstairs, using a “warm roof” means we can open everything up into it, so first floor rooms can feel spacious even with the eaves – and hence the lowest bits of ceilings – down level with the window head height of 2m. We’ve now got a much more generous space inside with less than a metre extra height at the ridge.

It would have been possible to counteract this increased height by reducing the pitch of the roof. However, at 30 degrees it’s already shallower than would have been common on older houses in the village, and reducing it further would make the house feel more modern and less like its neighbours. The height of the walls, and the eaves, is similar to other houses nearby, and the overall height would not look out of place.

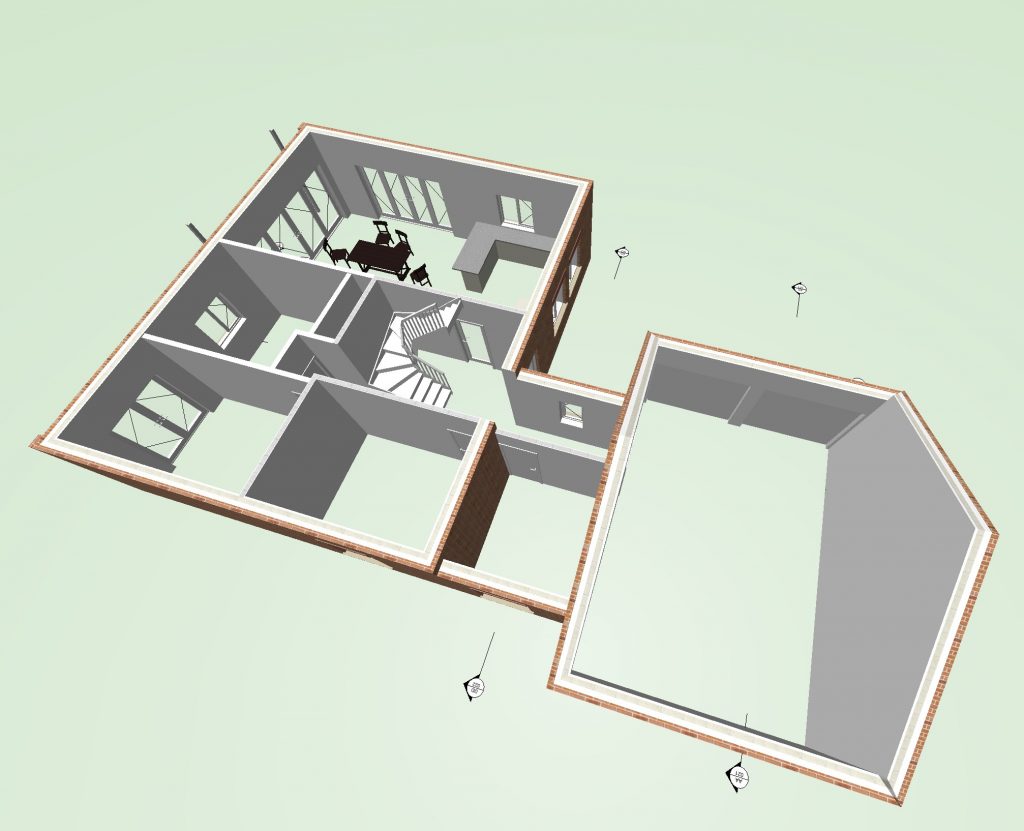

But how does this all work with the need to keep to the existing loadbearing wall locations? Well, we can keep the kitchen/dining room width the same, which retains one existing main wall. We’ll need one beam to pick up where the dining room wall shuffles forward, but that’s do-able. Retaining the loadbearing walls to the smaller rooms on the north side restricts the width of the hallway, but a quick check on where circulation routes will be needed – and simplifying that to a main straight east-west route – still leave enough room for a winding stair, just! This could be quite funky – a semi-circular winding section with straight top and bottom flights, so it needn’t be hugely wide, and I can model it simply as a placeholder.

The new living / dining / kitchen arrangements make those combined spaces slightly bigger than they were – which the clients like – but throws up the challenge of where to fit four bedrooms into apparently reduced space. At ground floor level there’s room for two small-ish guest bedrooms, plus a study, plus a shower/WC/etc. Upstairs though…? There’s room for a lovely main bedroom – again with views out towards the ponds, so we can keep the bed end a bit more enclosed with a standard window and pop a Juliet balcony at the far end for those morning “greeting the sun” moments – it’s facing east, after all. There’s room for an en-suite, and we’ll need at least a toilet for the living accommodation up there. There’s space for a bathroom/shower room in fact, but not for that missing fourth bedroom.

Unless… …the little link section between house and garage; what if that grew from being single-storey to one-and-a-half? That would give space for a bedroom in there, especially if we dropped the floor by a couple of steps – the link to the garage, and the utility room don’t need a 2.7m ceiling. I try it out and it works – initially just with a pair of rooflights but adding a wee dormer over the entrance area would help to make that more interesting and… …it all helps the approach side of the house feel more traditional – as if an existing building had been added to incrementally. The garden side – hidden from the public and neighbours – can be more contemporary and open; it’s still currently shown as brick but we can explore other materials. We have the beginnings of a revised scheme.

I’ve put a set of images of the work in progress above, but hopefully what you can see from the narrative before this is how that scheme evolved; the steps of rethinking where different functions go, and how they relate to the site and setting. The pondering 3D space and height and working out how that works with overall building height and massing. The testing of dimensions to ensure everything fits, and the balancing of the occasional compromise (that extra beam) to give freedom where needed. All of the above happened during a four-hour session; towards the end of that I was able to walk the clients through it via screen sharing on Zoom, and we looked at where sunlight would come into the building – adding a couple of extra windows and seeing the effect they had, and lining up half a dozen additional changes for when I next get it on screen.

Us architects (and other designers) can sometimes be a bit possessive about the process of design. I’m not suggesting that’s all bad – sometimes a bit of quiet is a productive thing, and some of that process above comes from a mix of lengthy training and thirty-odd years of playing with buildings and spaces. But likewise, for my clients (and for the community in public projects) understanding and being able to engage with that process can be really important – from simply being able to input good ideas from different perspectives, through to understanding the evolution of a design and its relationship with the brief, there are, I think, benefits in narrating the process and opening it up. What do you reckon?